The Commercial Open Source Playbook: How to Build a Business on “Free”

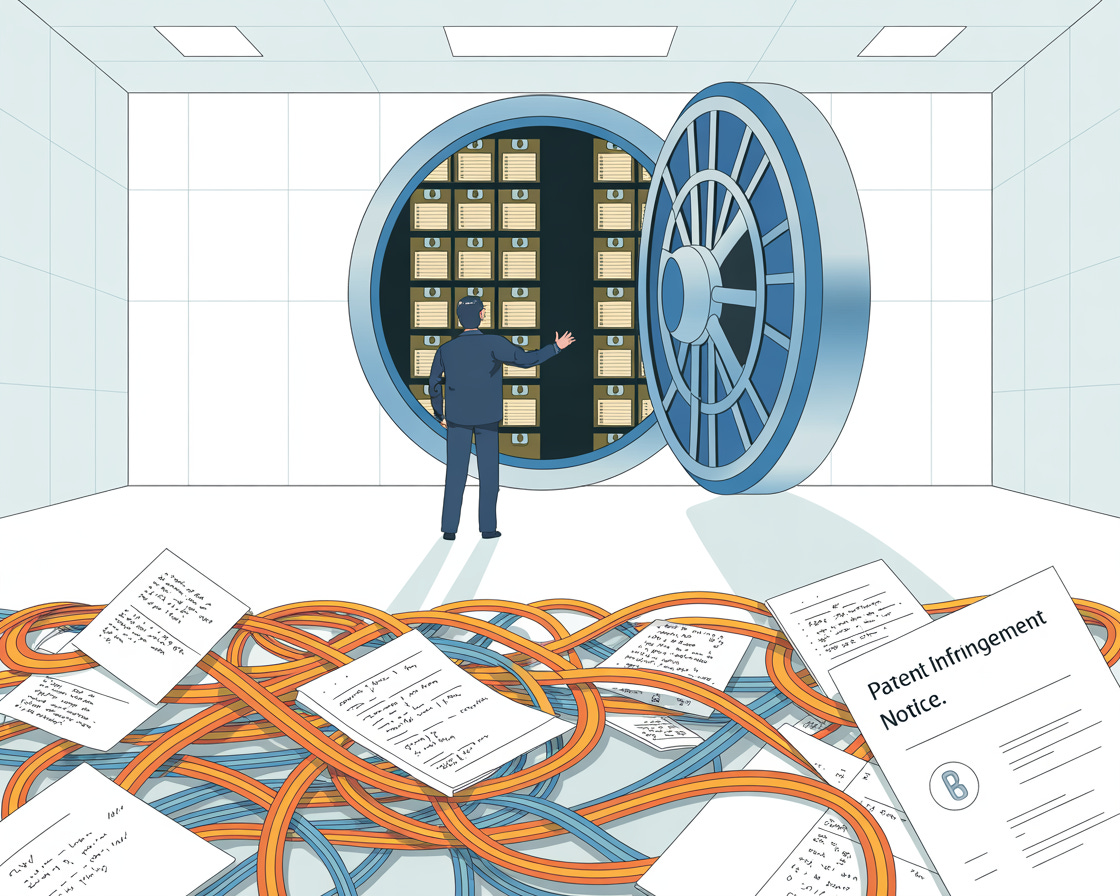

For decades, the software industry operated on a simple, restrictive premise: lock the code in a vault, charge an arm and a leg for a license key, and sue anyone who tries to copy it. Then came Open Source. At first, the suits in the boardroom dismissed it as a charity project for hobbyists. Then Red Hat went public. Then MongoDB, Elastic, and Confluent built multi-billion dollar empires.

Suddenly, giving away your “secret sauce” wasn’t charity—it was the most efficient customer acquisition strategy in the history of enterprise software.

But let’s be clear: Commercial Open Source Software (COSS) is more than a philosophy; it is a business strategy. It is a ruthlessly effective way to reduce friction, build a user base, and monetize the enterprise’s need for reliability. Here is the Kellblog take on how Commercial Open Source works, why it wins, and how to execute it without giving away the farm.

The Core Principle: Free Bits, Paid Insurance

The fundamental confusion about COSS is the difference between the code and the product. In a commercial open source model, the code is released under an OSI-approved license like Apache or GPL. Anyone can view, modify, and redistribute it. But enterprises don’t just buy code. They buy risk mitigation.

The commercial entity wraps that raw code in a layer of value that enterprises are legally obligated or operationally desperate to pay for. This creates a “Dual-Purpose” reality. You have the Community Edition, which is for the hacker, the student, and the startup. It is DIY; if you break it, you keep the pieces. Then you have the Commercial Edition for the Global 2000. It comes with SLAs, indemnification, security patches, and someone to yell at when the database goes down at 3:00 AM on a Saturday.

The business model relies on a simple equation: you achieve ubiquity via open source, and you achieve monetization via enterprise requirements.

How to Actually Make Money

If you are giving the software away, where does the revenue come from? In my experience, successful COSS companies generally leverage one of three dominant strategies.

The first is the Support-First model, pioneered by Red Hat. The software is 100% open, and the vendor sells a subscription for enterprise-grade support. The pitch is simple: “Sure, you can run the free version of Linux. But do you want to explain to your CIO why mission-critical production servers are unpatched?”

The second, and currently most popular, is Open Core (or Feature Tiering). Here, the “core” functionality is free, but certain enterprise essentials (e.g., security features, auto-scaling, auditing, etc.) cost money. This is the model used by Elastic, Grafana, and GitLab. The database is free, but if you want LDAP integration, audit logs, and high-availability tools—features only a large company needs—you need an Enterprise License. The rule of thumb here is that functionality is free, but manageability is paid.

Finally, we have the Managed Service (SaaS) model. The software is free to download, but difficult to operate at scale. Companies like MongoDB (with Atlas) and Confluent (with Cloud) pitch the value of convenience: don’t hire five expensive DevOps engineers to manage your own clusters. Pay us a monthly fee, and we will run our software for you.

The Strategic Weapon: Licensing

Founders often treat licensing as a legal box to check. That is a mistake. Your license is your business strategy.

On one end of the spectrum, you have permissive licenses like Apache 2.0 or MIT. These are “land grab” licenses designed for maximum adoption with zero friction. You want everyone using your code, and you don’t care if Google uses it to build a competing product.

On the other end, you have “viral” or copyleft licenses like GPL. These are defensive. They ensure that if someone uses your code, they have to contribute back, keeping the ecosystem honest.

More recently, we’ve seen the rise of “Source Available” licenses like the SSPL (Server Side Public License). While purists argue these aren’t technically open source, they solve a very specific business problem: they stop AWS from taking your free code and selling it as a service without paying you a dime. You choose a permissive license to grow the funnel, and a restrictive or commercial license to protect the revenue.

Why Go This Route?

Why would a VC fund a company that gives its IP away? The answer is Frictionless Customer Acquisition.

In the traditional proprietary model, you need a sales rep to get a prospect to even look at the software. In COSS, the developer downloads it, builds a Proof of Concept, and falls in love with it before a salesperson ever makes a call. The developer becomes your internal champion.

Furthermore, you benefit from the network effect. More users mean more bugs found and more features contributed. Proprietary software rots; open source software evolves. It also acts as a massive talent magnet. Engineers want to work on cool, open projects, meaning your hiring pipeline is filled with people who are already contributing to your repo.

The Risks and the Bottom Line

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention where this goes wrong. The biggest risk is the “Amazon Problem.” If your license is too permissive, a hyperscaler can fork your code, rebrand it, and sell it as a native cloud service, effectively cutting you out of the loop.

There is also the constant tension between community and commerce. If you lock too many features behind the paywall, the community revolts and forks the project. If you give too much away, nobody buys the Enterprise edition. It is a delicate balance, and maintaining the support staff required to service a massive free user base can be incredibly expensive.

The Bottom Line

Commercial Open Source is the ultimate “have your cake and eat it too” model. It gives you the distribution power of a viral consumer app with the contract values of enterprise software. It offers customers the transparency they crave and the reliability they require.

If you can navigate the licensing minefield and balance the needs of the community against the demands of the shareholders, COSS isn’t just a way to write software—it’s the best way to build a modern software company.